This is the Jurassic Radio Section of

The Broadcast Archive

Maintained by:

Barry Mishkind - The Eclectic Engineer

Jurassic Telecommunications, Part IV

Fessenden Gives Radio Its Voice

By Don Kimberlin

This is the fourth in a series titled Jurassic Telecommunications describing the late Victorian, non-electronic roots of modern telecommunications. Although the operational technologies have changed, the core technology and simple principles behind it have not. Most technology history fails to adequately chronicle those simple early methods and the gargantuan machines their developers often had to utilize.

March 12, 2000

Much of the public can name Marconi as the nominal "Father of Radio" and many might even have recall of his epoch-making transatlantic transmission of the single letter "S" in December, 1901. However, few know that a year earlier, on December 23, 1900, an even more prolific technologist first transmitted human speech by radio.

Like many technologists over time, Reginald Fessenden suffered considerable rebuff and even plagiarism of his advancements. In his later years, he wrote

"In my lifetime, I developed over a hundred patentable inventions including the electric gyroscope, the heterodyne, and a depth finder. I built the first power generating station at Niagara Falls and I invented radio, sending the first wireless voice message in the world on Dec. 23, 1900.

"But despite all my hard work, I lived most of my life near poverty. I fought years of court battles before seeing even a penny from my greatest inventions. And worst of all, I was ridiculed by journalists, businessmen, and even other scientists, for believing that voice could ever be transmitted without using wires. But by the time death was near, not only was I wealthy from my patents, and all of those people who had laughed at my ideas were twisting the dials on their newly bought radios to hear the latest weather and news."

Fessendenís Childhood Vision

Reginald A. Fessenden seemed destined to live a life of fighting the establishment. From the outset, he turned away from parental wishes and believed he had a singular childhood vision

"My parents despaired of me. They saw my future as a church minister or a teacher, but when I closed my eyes and dreamed, I saw an invention that could send voices around the world without using wires or cables. "There's no future in that," my mother told me, and she was both right and wrong."

After a childhood and school years criss-crossing the border between Canada and the U.S. to the point that both countries have their own sort of claim to him, Fessenden began his working years as a teacher in Bermuda. (Some sources claim he never really graduated from college.) In those childhood years, he was close to Alexander Graham Bell and observed Bellís telephone transmission experiments using telegraph lines borrowed from a Bell relative employed by the telegraph company in Fessendenís home area. He claimed to have seen his boyhood dream of wireless speech transmission at that time.

In Bermuda, he maintained an avid readership of "Scientific American" magazine, filling relevant clipping files for matters of interest to him. He developed a deep interest and personal admiration for Thomas Edison; one that eventually drove him to New York in hopes of a personal meeting and interview for employment in the Edison organization.

Reginald Fessenden

Born: October 6, 1866 - East Bolton, Quebec, Canada

Died: July 22, 1932 - Hamilton, Bermuda

His Edisonian dream was not to be so direct, however. The great man was too busy to see just anyone. Fessenden wound up getting a job as a tester for Edison in New York when he happened to be on the scene when a tester left the company. Fessenden blossomed in the job and work, and soon became the head tester, called out to solve a variety of problems.

Fessenden Teams With Edison

In that day and time, wealthy persons had private electrical generating plants, and fortune smiled on young Fessenden when he chanced to impress no less important a person than J.P. Morgan with his suggestions for improvement to the financial giantís power plant.

Morgan relayed his approval to Edison, who promoted "Fezzy," as Edison nicknamed Fessenden to be his personal assistant. There was important need for improved electrical insulating material because most insulating coatings of the day cracked when they dried out in the heat of operation. A better material was needed, and Fessenden came through, developing what he called "the dipole theory of elasticity," one of the basics of power insulating technology. By 1890, Edison had promoted him to the position of Chief Chemist. Fessenden now had access to perhaps the finest technical libraries of the time, and regularly met the illuminati of early electrical power Ė men like Lord Kelvin, Dr. Kennelly; George Westinghouse.

Westinghouse stole him away from Edison, offering a position supervising the work of developing generators. One should recall here that there was a huge dispute between Westinghouse favoring AC for power while Edison said DC was the way to go. This of course meant that Westinghouse had won Fessenden over to the AC power camp, which would be a bit of a personal affront to Edison.

Fessenden did, however, pay his new employer off by developing improved light bulb lead-wire technology that permitted Westinghouse to succeed at a landmark light bulb contract in 1892. During a visit to Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in northern England to see some newly-developed steam turbines, Fessenden remarked that an efficient way to use it would be with the turbines driving electric generators that would drive electric motors to propel ships of all sizes. That Fessenden vision became commonplace throughout the world of seaborne commerce.

By the time he returned from England to the U.S., he had so impressed the world of academe that he was offered (and accepted) a position as a professor at Perdue University. Now, Professor Fessenden was free to engage research in his own interests, which centered on sound vibrations and transmission of sound without wires. Of course, in this period, the work of Marconi, Lodge, Slaby, Arco and others was being reported as news.

Going It Alone

Within a yearís time, Fessenden was so enthused about his own technology that he resigned his Perdue professorship, ostensibly to work on his own inventions. George Westinghouse was still personally interested in him, however, and sent him one thousand dollars with the stipulation that Fessenden move to Pittsburgh to work in Westinghouse premises (which, as we know, would put him in close proximity to Nikola Tesla).

During his Pittsburgh tenure, Fessenden developed and patented a number of his own inventions in addition to his Westinghouse work. One of the personal developments was basic microphotography, which of course forms the basis of document preservation several decades later.

Wireless Weather (The First Radio Weather Reports?)

His central interest, however, kept returning to "wireless" and its technology. He tried and tested a number of methods seeking improvement on the Marconi way of generating wireless signals, which did have its crude points. By 1899, he had demonstrated a range of 50 miles from Cobb Island to Arlington, Virginia, and impressed the U. S. Weather Bureau into signing him to a contract for the (then) large sum of $3,000 per annum to develop wireless for weather information gathering.

It was in that first year of the Weather Bureau work that he finally developed a method to get the frequency of an arc transmitter high enough to handle barely understandable speech. Modifying a phonograph cylinder with nearly microscopic slits, he was able to interrupt an arc at 10,000 times per second, and on December 23, 1900, transmit a barely readable voice message over a distance of one mile on Cobb Island.

As well, he found contact radio detectors like the coherer too distorting and lacking in sensitivity for the reception of speech. He worked on a much more sensitive detector called the barreter, and fortuitously secured success in a second iteration by accidentally leaving a wire in an acid solution. The wire point in the cup of acid worked quite well. In fact, it worked well enough that Lee DeForest used it later in contravention of Fessendenís patent, resulting in a protracted legal battle between the two.

The Weather Bureau renewed his contract for two more years, and expanded the work to include extending the wireless link to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. During this time, Fessenden set General Electric to work on producing an AC generator that would emit frequencies high enough for use as voice-bearing wireless. The experiments were many and trying; it was only by using methods like Edison had shown in developing his light bulb that success occurred, bit by bit.

By 1902, General Electric had managed to produce a 10 kHz alternator for Fessenden. It was used transmit telegraphy by tones over a 50 mile path between Buxton, NC (the town located at Cape Hatteras) and Manteo, NC. Visitors to the area can see state highway historic road signs commemorating the event at each place. Unfortunately, Fessenden got into a dispute over ownership of the ideas with Federal employees and he resigned the job in order to keep his personal inventions.

Financial Backer Support Leads to Formation of Public Telegraph Companies

His reputation remained at Pittsburgh, however, and two financiers agreed to back him in forming the National Electric Signalling Company, provided he donate his inventions to the company. Two transmitters were soon built on Cape Cod (where Marconi also had a transmitter) and following their success, stations were built in New York, Philadelphia and Washington, with a plan to enter the public telegraph business by radio. In doing so, Fessenden created a radio "first" by transmitting messages overland for large distances. He even beat out Marconi in distance by having a message heard almost 6,000 miles away in Alexandria, Egypt. Successful contracts with United Fruit Company led to National Electric Signalling placing radios in New Orleans, on board United Fruit ships and in the United Fruit banana plantations of Central America. All this formed the beginnings of the Tropical Radiotelegraph Company, ultimately the fourth largest international telegraph company of the United States.

International Extensions and The Worldís First "Broadcast" by Radio

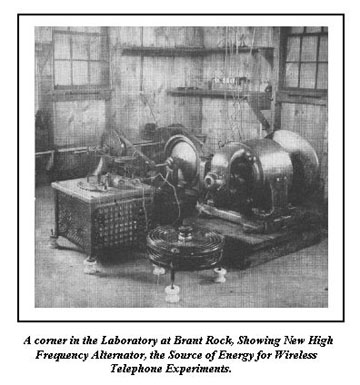

To engage international telegraph business, National built a duplicate of its Brant Rock (Cape Cod) plant at Machrihanish, Scotland. There were start-up problems, however, until Fessenden sent his best assistant, a Mr. Armor, to Scotland. Within two weeks, Armor sent a cable telegram that Brant Rock was being heard loud and clear in January 1906. Fessenden continued development work (that by this time was trying the patience of his investors, who wanted business, not science) to secure more efficient alternators and antennas on ever higher frequencies.

By June 1906, regular speech transmissions between Brant Rock and Plymouth, MA were going on. In November, Armor messaged from Scotland that he had clearly heard the a conversation involving Mr. Stein at Brant Rock telling the operator at Plymouth "how to run the dynamo." This then, goes down in history as the first reception of human speech across the Atlantic.

The alternator that Charles Steinmetz and later Ernst Alexanderson had by now developed for Fessenden was capable of being run up to 100 kHz with an output of 1 kW. For most operations, it was only run to 60 kHz with about 250 W output. By December 21, 1906, Fessenden was demonstrating Nationalís speech transmissions to telephone people. On December 24, 1906, Fessenden produced what broadcasting textbooks acclaim as the first broadcast of a program of music, readings and entertainment by radio to a tiny audience largely comprised of ship radio operators, most of whom were astounded to hear voices in their earphones. The "broadcast" was repeated on New Years Eve, 1906.

Fessenden Turns to Maritime Electronics

During that highly inventive year of 1906, Fessenden could even lay claim to having invented radiopaging, as he built a "beeper" into the hats of his Brant Rock workmen to signal them using his radio transmitter.

However, business difficulties loomed larger and larger in the form of disputes with his financial backers and the loss of antenna towers at Scotland, taking National back out of the transatlantic telegraph business. Fessenden got into a mire of legal disputes, and shifted his work interests to underwater sound, moving to work for Submarine Signal Company at New London, CT.

At Submarine Signal, he once again innovated, and produced a fathometer which by World War I was a useful device for detecting enemy submarines, as a rudimentary form of sonar. Following the sinking of the Titanic, Fessenden claimed to have "bounced" radio signals off icebergs, creating the foundations of radar.

Fessendenís work at National Electric Signalling eventually flowed through into the new Radio Corporation of America at its founding in 1919. It became the basis of RCAís set of 200 kW alternator radio transmitters for global radiotelegraph business operated by David Sarnoff.

Retirement to Bermuda

After WWI, and after some years of fighting a number of legal battles, he retired to Bermuda where his interests turned to mysticism, much as had Oliver Lodge in later years. His grave there contains the paean

"By his genius distant lands converse and men sail unafraid upon the deep."

Below that line, Egyptian glyphs proclaim

"I AM YESTERDAY AND I KNOW TOMORROW"

Does that mean the spirit of Reginald Fessenden walks among us as we speak on cellphones today?

Want to know more?

(1) Thereís a website that recreates the sounds of various types of spark transmitters, reproducing what the first speech transmitted by radio may have sounded like on December 23, 1900. (The sound files are in .AIFF format, which requires either an Apple PC or Quicktime for Windows to play) http://www.hammondmuseumofradio.org/spark.html

(2) A Fessenden biography: http://www.hammondmuseumofradio.org/fessenden.html

(3) Thomas White's website includes a contemporary review of Fessenden's Brant Rock speech transmitter dating to a few days prior to its historic first "broadcast" on Christmas Eve, 1906. http://www.ipass.net/~whitetho/fess1907.htm

(4) Marinaers know the marine radio name for Cape Hatteras is "Buxton Radio." Few, however, know that descendant of Fessenden claims to have been first to hear the sinking Titanic http://coastalguide.com/packet/buxtonradio.htm

For the book readers

(1) "Radio's First Voice The Story of Reginald Fessenden"' Ormand Raby, MacMillan of Canada, Toronto, 1970 (No ISBN)

(2) "Fessenden, Builder of Tomorrows" Helen M. Fessenden, ARNO PRESS - a New York Time Company - 1974 ISBN 0-405-06030-0

Don Kimberlin has written many articles about his experiences over the years, as well as those who were the pioneers in the telecommunications and broadcast industries.